|

"In simplified games, you want them to be forced to play tightly because simple mistakes can be incredibly punishing. Good, solid, foundational gameplay is probably the most difficult to maintain way to win, and you want your opponent to feel that pressure. Therefore, using your removal efficiently should largely focus on the ability to remain in the game when in these simplified positions." Card advantage is a simple analysis of who has more resources. As far as fundamentals of TCGs go, I’d say card advantage is at the top of the list of things people learn, before concepts like risk, beatdown, and making reads. But card advantage is very limited and difficult to analyze properly in game because there are a lot of variables that go into what makes a card “real.” So, I don’t really care about it in a traditional sense. Instead, its importance lies more in what cards tell you to do outside of game mechanics, and how they’re forced to interact with one another. A game of Yu-Gi-Oh! can be reduced to a number of necessary trades in which the victor is the player who consistently makes the better end of the deal. But trades aren’t always equal, and trading doesn’t mean you get what you want in return. This is where understanding the Philosophy of Greed comes into play. Generally speaking, you have three options with how you can deal with a card: you can use Pot of Greed on it, you can use Jar of Greed on it, or you can make it a Dark Deal, which is where this theory draws its name. What this means is simple: You can trade up with a card by gaining advantage, you can trade with it by equalizing, or you can make a concession to trade down, to make sure it can’t hurt you anymore.

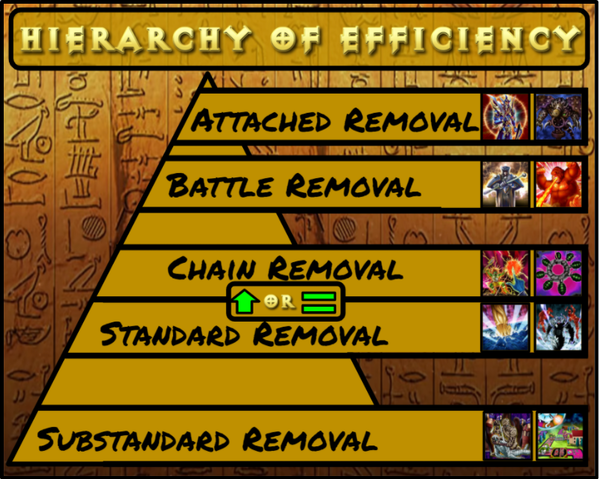

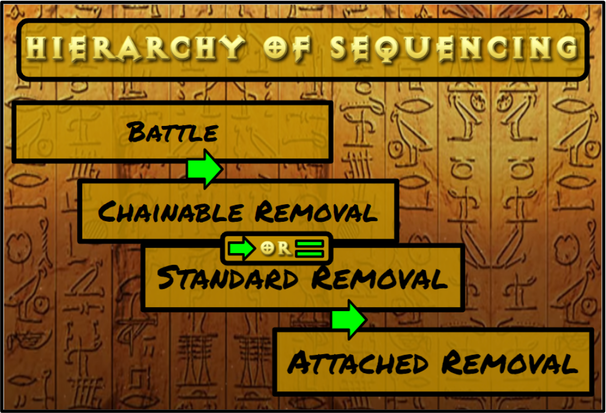

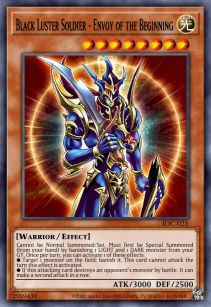

Summoning Dekoichi means the opponent is going to have to deal with him. If they can’t or refuse to, they lose the game. This is an unwritten effect Dekoichi shares with numerous other cards in the format. They have to be dealt with, often at a disadvantage to the opponent. Cards like Dekoichi force players to make a Dark Deal or settle for Jar of Greed, which is precisely what makes them good. Let’s say our opponent attacks with a flipped Dekoichi. If we Saku it, we’re -1, like it or not. We traded a card for a floater, when instead we can equalize through battle. Why give up Saku for Dekoichi when we can summon Kycoo, beat over it or force one of their responses, and lose nothing in the process? (Well there are many reasons, but ignore them all right now). In other words, some forms of removal are more efficient than others, and you should opt to use your cards more efficiently. I even made a chart: Monsters are usually the best. At everything. They’re capable of gaining advantage multiple times if not answered. Every time one kills another in battle, it continues to live. The opponent still has to deal with it, and now it puts them at a disadvantage they weren’t at if they had done so sooner. A monster being large can cause a snowball effect over the opponent if left unchecked. This is a cornerstone of the aggro strategy, where simplifying the game by removing backrow with backrow and monsters with monsters is the game plan of choice. Likewise, attached removal (such as Black Luster Soldier) continues to exist on the field after use. This means that an inability to answer these cards once will be met with a difficult time answering their subsequent uses, especially since they don’t require the Battle Phase. Chainable removal is at least equal to and often above removal like Smashing Ground in terms of efficiency. This is because these cards can be made advantageous by chaining them to an opponent’s cards. Cards like Smashing Ground can never do that since they’re spell speed one. The higher the tier of removal that a card mitigates, the stronger the card tends to be. It either demands a more efficient answer, like TER, or a less efficient one, like Raigeki Break. Sequencing your removal is also important, as there are a lot of cards that punish your better means, such as Snatch Steal. The hierarchy of efficiency of sequencing is as follows: Substandard removal isn’t up here, because we don’t play bad cards. And, like any other rule in Yu-Gi-Oh!, you’ll probably break it more often than you’ll abide by it. But hey, it’s still good to keep in mind. The real use of this rule is understanding how cards play roles in determining how and why removal gets used, and how to capitalize on mistakes to nullify Pot-Duo openings. Almost every card in this game has an unwritten effect that determines what they actually do when they hit the board, or, even better, displaying the threat of what they could do. There’s a lot more to a card than the text written on it. A common unwritten effect to be wary of is BLS. Black Luster Soldier doesn’t let you play answers to him until he’s been answered. A well-played BLS ends a game on the spot. It’s oppressive and demands an answer, and while on the field he carries an effect that denies the opponent the ability to set monsters. Then, he punishes them with 3000 damage if they don’t. Answering him is absolutely imperative; if you can’t, you lose. There’s a saying in chess that states, “the threat is stronger than the execution”. BLS is the prime example of this phrase in action. Think about all the cards that you most certainly play with BLS in mind: Snatch Steal, Ring of Destruction, and your own BLS to name a few. There’s no hard rule in the game that says you can’t play these cards before BLS is summoned; it’s just a thing we know we should be wary of. But when BLS is played, and one of these cards is used on him, we wonder what we were afraid of since we have these cards in our decks.

With 1900 Attack, four swings is 7600 damage; you aren’t likely to come back from that. His defense stat is also a respectable 1700 which walls the absolute majority of the format. Very few presently main-decked monsters get over him. That is, of course, barring a chaos monster, but that’s what we want isn’t it? Meanwhile, Kycoo’s a strong dark monster that basically can’t be banished and prevents a chaos player from using their best cards. But if I can give you one of the most important mathematical facts I know, it’s that 1900 is in fact more than 1800. Skilled Dark’s ability to kill almost anything, including Kycoo (especially Kycoo), is insane when combined with his dark attribute and high defense. He’ll always take at least one card, hopefully a forced TER or Sorcerer, down with him. You can look at Skilled Dark Magician like a sort of Chaos Sorcerer specifically for Kycoo, or like an MST for Sakus and Breaks. Effectively, in terms of advantage, Pot of Greed and Jar of Greed, respectively. These are the chains of interactions that cards can be re-framed as in order to better understand the value you’re obtaining. If you can consistently make solid Pot of Greed trades, you’re capable of coming back from scenarios where your opponent played the actual card, maybe multiple times.

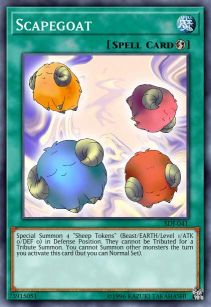

player can just let Spies sit there while they put their own out and deny both players a battle phase; a warrior player has no such luxury. But Jar of Greed isn’t a bad card. Not every interaction needs to become a Pot of Greed, and you can’t benefit in every trade. Sometimes, your best play is to simply deal with a card. While optimally we could always gain pure advantage, it doesn’t work out that way. Let’s imagine we’re facing down a Dekoichi and our opponent has no backrows. Our hand contains Tsuk and NOC, but no other monsters. We have 4 options. We can Tsuk it and run over it, Tsuk it and NOC it (and do 1100 damage), set Tsuk, or, we can do nothing and let another turn of 1400 damage pass. Both of the removal plays are a Jar of Greed with no way to counteract it. We either spend one card to kill theirs, or kill one of theirs to give them another. Assume the other three cards in our hand are Thunder Dragon, Scapegoat, and Book. With Scapegoat, we don’t have to worry about a random loss to BLS on damage, and setting it means the opponent will likely not summon the BLS. However, we have to question what we lose in a specific line of play. If we don’t set Tsuk and continue to eat 1400 every turn, we eventually have to give up another card to Dekoichi, being Scapegoat. Dekoichi now gained a card, and by pressuring us, took another one. If the Scapegoat doesn’t have a good follow up like Metamorphosis, what are we doing? Even if it does, do we really want to spend TER on Dekoichi? We can nullify the majority of damage and cost by destroying the Dekoichi now or setting the Tsukuyomi. Destroying it now takes us off the clock but you’re giving your opponent more cards off their floater. That sucks pretty bad. NOC’ing takes away options to use it on better cards. That sucks even worse. And, even though a BLS isn’t going to kill you through Scapegoat, using it should be a last resort when you can stall the game out by setting Tsuk. You shouldn’t be afraid to settle for less when it can get you more later. Setting Tsuk loses to NOC, but you’ll lose to NOC when you set a real monster anyway. Setting Tsuk loses to BLS, when you could hold it to remove BLS, but by the time you have to Tsuk-NOC a BLS without a chaos monster in hand, you’ve lost anyway. By setting the Tsuk, we give away no cards for free, unless they have like Breaker or something, and we give away no correct information. If Dekoichi can’t kill our Tsuk, and they don’t have NOC, then we’ve actually taken away the right for Dekoichi to continue calling itself a real card. See, not allowing your opponent’s monsters to attack effectively removes their value as cards. When I first discovered, and if anyone tries to say otherwise I’ll beat them up, Skilled Dark Magician in 2016, the choice deck of Goat Format was still Goat Control. Airknight Parshath was the mini-boss of choice, and no one thought much of Sorcerer yet. I said to people, “This guy is big, he’s dark, he’s basically Exarion, and he walls Airknight in attack position.” Walling in attack position is a strange stance to take on a card when everyone’s playing two Book of Moon and two Tsukuyomi, but at the time it was our coolest option for dealing with Airknight (alongside Skilled White Magician). The Skilled brothers both had a large showing when we were dropping Exarion from the format, but I thought dark was better among a field of people convinced white would just be superior. Thing is, white can’t do anything to Airknight; it can only wall it. Dark can wall it, crash with it to turn it off on your own terms, and above all else, beat all those silly attack position Skilled Whites. Airknight costs a lot to summon and losing it can be devastating. But losing it can mean a lot of things outside of “this card was sent from the field to the graveyard.” An Airknight that can’t attack is what we would call “not very good.” But, the problem was that Skilled Dark’s defense is a bit small compared to the attack stat of Airknight.

Firstly, it’s a chainable. It’s more than possible to get value out of it if your opponent targets it or your monster. It also saves your monsters from battle to run the attacker over later. Book of Moon is a key component in the necessary trades that comprise Goat Format. Let’s analyze Book on probably the most common interaction it has: Chaos Sorcerer vs. Chaos Sorcerer. Chaos mirrors often play out like an unfolding game of chicken where the first person to drop a Sorcerer on board is the one who loses the standstill, and as a result, the game. Book of Moon is an insurance device that means your Chaos Sorcerer is protected for a full turn barring NOC or another Chaos Sorcerer. This is an instance where it’s obvious that card advantage ends and position begins. If you’re the last person with the ability to make a trade up, its because you were the last person with a real card to give away. If your opponent has no more cards to give up to protect their Sorcerer, then that’s the card they’re forced to give up; and being forced is, well, the opposite of good. You could even say it’s bad. If you’re the last person who can make a choice, then you have all the value you could want or need. Card advantage only matters when calculating real cards, and cards aren’t real until their effects have been realized in a way that gains either strict value or positional value, like Book of Moon. Cards like Thunder Dragon and Sinister Serpent are widely known non-real cards until you see Graceful or Raigeki Break. But, there are plenty of other situations where nonreal cards are less apparent. A surface +1 like Duo can easily be rendered an effective +0 or even -1 when your hand contains Serpent (or no cards at all). Cards that solely take from the opponent have diminishing returns as a game moves forward, and this isn’t limited to discarding effects. Every MST or Dust Tornado you control becomes a liability as Heavy Storm approaches when your opponent has no backrows. They do nothing when unable to use their effects, and they can’t deal with monsters, which are the cornerstone of winning a normal game of Yugioh. While it is important to remember that they can be useful in the future, they presently do very little to benefit your position, outside of perhaps fooling an opponent.

to be able to deal with it. If I’m up on the draw, I can use Saku to keep the pressure of my normal summon up. I also have to consider how many life points I have because no amount of cards is worth letting those hit zero. It’s important to be able to quickly identify who’s presently in control. A warrior player with a single Blade Knight is beating two Thunder Dragons and a Sinister Serpent. That’s almost ideal for the warrior player actually. He’s obviously lower on cards but his live card count is one and his opponents’ is zero. Trading down continuously serves to work in his favor, until the chaos player draws a Sorcerer. The constant pressure from his single real card as well as his turn draw can do more than any number of Thunder Dragons can. This is one of the key reasons warriors are considered favored in this matchup, whether they actually are or not: All of their cards do something; not all of a chaos player’s cards do. Finally, I said earlier that one goal of sequencing removal is to dodge the most punishing cards in the format. While this is true and a necessary thing to keep in mind, it’s not the ultimate arbiter of when to use certain cards. An even bigger reason to save your more powerful cards, if possible, is that a large number of them are your biggest threats. If you expend them early, you lose the majority of your threat density in the late game. The fewer cards the opponent knows you can push with, the more loosely they can play without worry. In simplified games, you want them to be forced to play tightly because simple mistakes can be incredibly punishing. Good, solid, foundational gameplay is probably the most difficult to maintain way to win, and you want your opponent to feel that pressure. Therefore, using your removal efficiently should largely focus on the ability to remain in the game when in these simplified positions. Entering an endgame holding BLS will benefit you much more than holding a Dekoichi and Sinister Serpent. A key factor of solid technical play is planning ahead, as much as respecting your basic gameplay concepts. While it may seem reductionist to treat Yugioh like a game of checkers, where the sole goal is to remove all the opponent’s pieces and king your own, it isn’t far from the truth. Making the correct trades is positional. It's focused almost solely on the advantage that giving up one card for another (or just straight taking them away) can give you. Pot of Greed on turn one isn’t a death sentence. Neither is Delinquent Duo. Even both combined doesn’t have to be. Those are strong openings and the combination of them is unlikely but not so much so that you shouldn’t bother learning how to play out of them. It’s criminal that so many players turn away from Goat Format because of these cards, when the amount it has to offer from a learning and enjoyability perspective is vast compared to almost every other format. To sum up the Philosophy of Greed: Cards that pressure demand answers, and cards that demand answers often manifest as looming threats that do a lot more than they say on the card. Some cards are more powerful than others, and that power means that even when they can gain clear advantage, being too greedy can put you in a bad position later on. Furthermore, every decision must take your non-card resources into account. Every interaction between cards gives you the opportunity to satisfy your own greed, be it with a Pot or a Jar, and correctly identifying the cards that demand those particular trades will lead you to victory. Final Notes:

7 Comments

Person

2/22/2021 12:27:04 pm

Book of Moon isn't worth a deck slot.

Reply

Matthew C.

3/3/2021 08:06:09 pm

Yeah! Nobody reads anything. Books? -Get that ish out of here. Play ready for interception cause your plays aren’t going through.

Reply

tanaz

3/5/2021 01:46:58 am

this was long

Reply

al martinez

12/5/2021 07:17:35 pm

amazing read, thank you for this very useful info

Reply

salty boy

11/9/2023 09:40:01 am

all good and planned, so bad that there are allowed cards like pot of greed and delinquent duo that completely destroy the format and make everything bland and disappointing.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

Upcoming Live Events (Goat Grand Prix) Tournament Coverage/Deck Lists Goat Grand Prix Application Hall of Fame Play Online Strategy: Advanced Strategy: Beginner Tier List Archives

July 2024

|

Copyright © 2015

RSS Feed

RSS Feed